Sciatica – Januaury 2017

On Tuesday January 17th 2017, Queen Square Private Healthcare welcomed an audience of General Practitioners and primary care givers to the lecture theatre in Queen Square for the first event in the 2017 programme of GP Seminars.

For this event, we were pleased to welcome Mr Jonathan Hyam, Consultant Cranial and Spinal Neurosurgeon at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, who kindly prepared a talk on Sciatica and the clinical patterns of radicular compression.

Sciatica, a pain that radiates along the path of the sciatic nerve, has a lifetime incidence of between 13-40% and represents a signification proportion of all presentations reported in general practice. Sciatica-type pain is most often characterised by one or more of the following symptoms:

- Constant pain in only one side of the buttock or leg

- Leg pain that is often described as burning, tingling or searing

- Weakness, numbness or difficulty moving the leg, foot, and/or toes

- Pain that radiates down the leg and possibly (but rarely) into the foot and toes

The physical and social burden of sciatica is high, with 30% of sufferers experiencing persistent pain for longer than one year and 20% out of work due to the condition. Between 5-15% of sufferers will require surgery.

Sciatica is not a medical diagnosis in itself but rather a symptom of an underlying condition, with the most common causes being compression or irritation of the nerve roots by degenerative disc disease, spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis.

The Sciatic Nerve

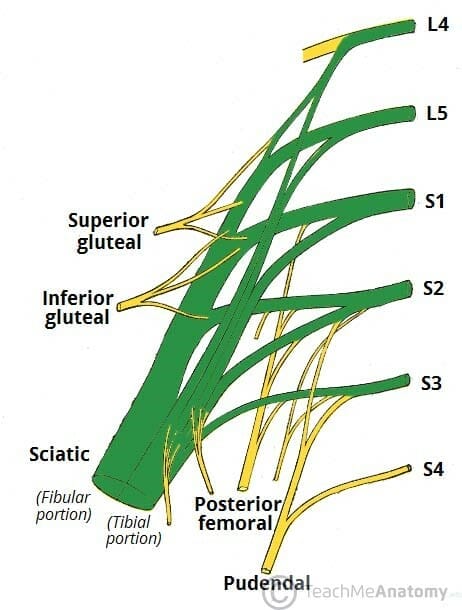

The largest single nerve in the body, the sciatic nerve is made up of individual nerve roots which originate from the lower lumbar and sacral spine (L3/4 to S3 segments) which then combine to form the sciatic nerve itself (figure 1). Most commonly, symptoms of sciatica are caused by compression of the nerve roots, rather than the sciatic nerve itself.

Figure 1. The sciatic nerve roots of the sacral plexus (Green)

The individual nerve roots exit the spinal canal and unite to form the single nerve in front of the piriformis muscle. The nerve passes through the greater sciatic foramen, exiting the pelvis, and travels down the posterior thigh to the popliteal fossa where it then divides into two branches:

- The Tibial Nerve – travelling to the posterior compartment of the leg into the foot

- The Common Peroneal Nerve – travelling down the anterior and lateral compartments of the leg into the foot

The sciatic nerve supplies sensation to the skin of the foot and entire lower leg (except for its inner side) and innervates muscles, in particular:

- The muscles of the posterior compartment of the leg and sole of the foot (via the tibial nerve)

- The muscles of the anterior and lateral compartments of the leg (via the common peroneal nerve)

The specific sciatica symptoms largely depend on where the nerve is affected. Clinical examination is crucial to identifying such symptoms and Mr Hyam explained that examination may test the hypothesis as to the location of the cause of symptoms using tools such as the ASIA Score.

ASIA Score

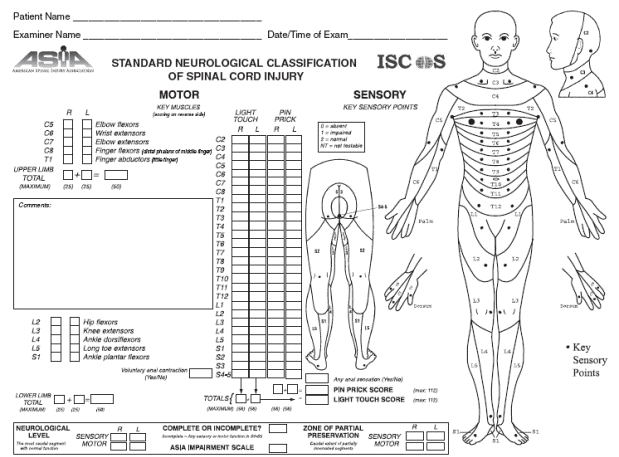

The ASIA score was developed as an essential neurological assessment for all patients with a spinal injury/condition. It consists of strength assessment of ten muscles on each side of the body, and pin prick assessment at 28 specific sensory locations. Through an understanding of myotomes (areas of muscles innervated by a single spinal nerve root) and dermatomes (an area of skin that a single nerve innervates), the information gained through this clinical assessment may be assimilated for determining a single neurological level (Figure 2)

Figure 2. The ASIA Score

Myotomes

My Hyam explained the use of an understanding of the myotomes of the sacral nerve roots to identify potential neurological levels for spinal disease. Concentrating on the L4/5/and S1 myotomes, simple clinical examination may be used to readily identify deficiency in:

- The ankle dorsiflexors – extension/flexion of the ankle as a potential L4 root compression,

- The Extensor Hallucis Longus – movement of the big toe as a potential L5 root disturbance or,

- The Plantarfexors – walking on ‘tip-toe’ as a potential S1 root disturbance.

He explained that in the presence of sciatica, deficits in the hip and/or knee flexors would not make clinical sense, since these myotomes are innervated by the femoral, not sciatic nerve roots.

Dermotomes

Similarly, knowledge and understanding of the dermotomes of the sacral nerve roots is essential. Again, the L4/5 and S1 dermotomes are most relevant to sciatica, and pin prick testing of the medial and lateral malleoli and sole of the foot are the most reliable and stable methods of examining sensation.

- Medial Shin/Malleolus deficit – L4

- Lateral Shin/Malleolus deficit – L5

- Sole, little toe deficit – S1

Mr Hyam explained that thorough clinical examination using the ASIA score, and an assessment of the symptom burden on the individual patient, should guide decisions about imaging specific spinal levels with techniques such as MRI, in the hope that imaging may reveal the cause of the symptoms and direct treatment.

Cauda Equina Syndrome

My Hyam then proceeded to discuss Cauda Equine Syndrome, a serious neurological condition in which compression of the lumbar plexus nerve roots below the termination of the spinal cord causes loss of function and symptoms which may include severe pain, saddle anaesthesia, bladder and bowel dysfunction, sciatica type pain, sexual dysfunction, absent reflexes and gait disturbance. My Hyam explained that such symptoms are known as the ‘Red Flag’ symptoms of cauda equina and warrant urgent referral.

The cauda equina is the name given to the bundle of all spinal nerves and nerve roots which arise from the conus medullaris of the spinal cord (L2 – S4). The nerves that compose the cauda equina innervate the pelvic organs and lower limbs, including motor innervation of the hips, knees, feet, and anal sphincters, as well as sensory innervation of the perineum. In cases of compression of the cauda equina, both sensation and movement can be disrupted and the nerve roots that control function of the bladder and bowel are especially vulnerable to damage. Without urgent treatment, there is a risk of permanent paralysis, impaired bladder and/or bowel function and loss of sexual sensation. Importantly, only lower motor neurones exist below the level of the conus medullaris. Therefore, patients with cauda equina syndrome should not display any upper motor neurone features.

The most common cause of cauda equine syndrome is intervertebral disc herniation in the lumbar region. Disc herniation can result in the soft centre portion of disc pushing outwards and exerting pressure on the immediate nerve roots.

Summary

My Hyam summarised by stating that the presentation of sciatica can be varied, and that even a cauda equine syndrome may be slow onset, with months passing before a patient’s condition becomes a complete case.

It is essential that the clinician applies an understanding of the neuroanatomy in their assessment of symptoms, and that tools such as the ASIA score are useful guides for the localisation of compression and the targeting of treatment. Symptoms and signs must correlate to the roots implicated on MRI.

My Hyam then took questions from the audience.

Q: Some imaging reports that we in clinic can suggest the presence of a cauda equine syndrome, despite the patient not presenting with symptoms of one. How should this be approached?

A: It is possible to have a slow and chronic compression of the cauda equina, with a certain degree of functional compensation. Therefore, imaging may demonstrate dramatic findings of a cauda equina compression, even though this may not correlate with the presentation. Acute disc prolapse is largely always the cause for cauda equine events that warrant urgent referral, and bladder/bowel dysfunction, anal sphincter tone and sexual dysfunction should always be regarded as ‘red flags’.

Q: Are we requesting MRI too much?

A: Whilst the ability for GP’s to refer for MRI is empowering and can provide reassurance, there is a problem when symptoms such as sciatica can be transient, and may have ceased before the scan is performed. In cases such as this, the scan results may not help as they will not correlate with the patient’s current condition.

Q: Should we be referring to Physiotherapy, or Osteopathy?

A: Whilst patients do report a benefit from treatments such as osteopathy and acupuncture, which are also not deemed to be unsafe, there is more Level 1 evidence to support the use of physiotherapy for the treatment of back pain. It is suggested that Physiotherapy should be used as a first line of treatment, since core stability strengthening has clear long term, as well as short term benefit.

Q: How long should we wait before considering a referral for back pain?

A: This largely depends upon the individual patient and their specific degree of burden. Management should be tailored to the individual, although any motor or visceral function disturbance should always be regarded as a ‘red flag’ for immediate referral. If back pain is accompanied by sensory disturbance (i.e. soft signs), then a programme of conservative management may be followed, although the patient may benefit from a consultation with a view to the use of a steroid injection. Surgery cannot cure back pain unless there is a physical abnormality to which the symptoms can be attributed. Physiotherapy remains the best course of action for back pain, where gradual strengthening helps to relieve symptoms and prevents future relapse.

Q: Is piriformis syndrome still part of the differential?

A: Yes, piriformis syndrome, along with other rarer causes such as hip dislocation may all cause sciatica. However, spinal disease should be ruled out first.

Q: How effective are steroid injections?

A: Epidural or nerve root injections are now a common form of treatment. The local anaesthetic used will provide around 12 hours of immediate relief, whilst the anti-inflammatory component provides longer term benefit. Some patients will experience complete and permanent relief after just one injection, whereas some may only experience temporary relief. In these cases, successive injections may be considered. In some rare cases, injections may worsen symptoms. Therefore, results are variable but mostly beneficial, with most patients experiencing relief.

We are very grateful to Mr Hyam for sharing his expertise with us on this topic, in what was a highly engaging and interactive session. For those wanting further information or wanting to discuss a private referral, Mr Hyam can be contacted through Queen Square Private Healthcare, or directly via his profile on our consultant search directory.

The next Queen Square GP Seminar will take place on Tuesday 7th March 2017, when Dr Hadi Manji, Queen Square Consultant Neurologist, will present on a tailored approach to the neurological examination.